MartinMargiela’s tenure at Hermes

In March 1998, an article in The New Yorker describes a visit to the Hermès museum on Rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré. There, admidst the troves of spurs and whips and coachman jackets, the musuem’s curator Ménéhould de Bazelaire reached for an apothecary bottle labelled “L’huile de pied de boeuf.” Holding the murky glass of Victorian-era saddle polish, she observed: “Very Martin Margiela.”

While the pharmacist aesthetic of this bottle was a token of Margiela’s own house, its contents were a nod to his new gig. Weeks earlier, the Belgian iconoclast’s first collection for Hermès had effectively polished the world’s most expensive saddle, the luxury house known for its equestrian history. Yet Margiela’s first collection at Hermès was somewhat of a cool- down compared to the buzz that surrounded his appointment. In 1994, Tom Ford’s arrival at Gucci set off a wave of young designers helming large European houses, a revolving door that continues to turn today. After Ford, John Galliano took the reins at Christian Dior, followed by Alexander McQueen at Givenchy. Yet none of these appointments stirred more curiosity than when Martin Margiela was announced as the head designer of Hermès, a presumed match-made-in-hell between fashion’s biggest iconoclast and the world’s most established luxury house. Headlines with the word “anti-fashion” proliferated, but at the time, Hermès CEO and heir Jean-Louis Dumas saw the designer’s arrival as the coronation of a lucid philosopher king: “I think Martin Margiela has a good idea of who we are. He sees through us better than ourselves.”

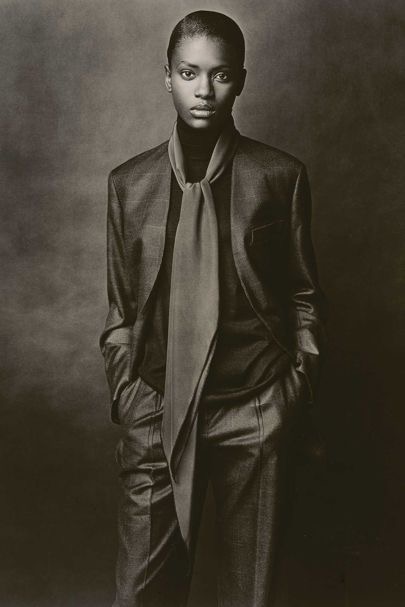

As a moment in the history of fashion, Margiela’s tenure at Hermès can best be seen in contrast to the time Marc Jacobs spent at Louis Vuitton, an appointment that occurred in the same year. While Jacobs’s logo-maniacal adventure at Vuitton brought luxury into a pop cultural stratosphere that it had never reached before, Margiela’s work at Hermès was a process of radical distillation. Prints were abolished. Silk scarves were locked in storage. And colors were replaced by “tones,” wherein the designer conducted a luxurious symphony of blacks, browns, beiges, and grays. In lieu of logos, he created a six-hole button that would shape its thread into an almost invisible “H,” a scarily succinct union of brand and function. During his time at Hermès, Margiela operated under a three-pronged mantra of “quality,” “comfort,” and “timelessness,” the second of which was perhaps the most surprising in the ever-stilettoed context of designer fashion. All told, his designs for the house were a devastatingly chic vision of coziness, created for a woman so well-to-do that she travels with her entire living room. As Cathy Horyn cited in a review of his first presentation at the house, their effect was a subtle invasion into the hyper-luxury milieu: “[O]ne way to appreciate his clothes is to think of them as the sorbet course in a heavy French meal. After a jolt of sex, a blast of color, you need something plain to cool you down: a shirt- waist dress in crisp black cotton, a slightly oversize poplin jacket worn with buff suede trousers, or maybe a halter-style cardigan over a bare-backed shirt. Coming from Mr. Margiela, who immoderately keeps things covered up, this could almost qualify as a sinful treat.”

Margiela’s collections at Hermès did not stir the same deconstructionist shock and awe that his legendary presentations for his own house did. His tenure there is thereby a moment that has remained largely hidden from public consciousness, one explored thoroughly in Lannoo’s catalogue Margiela: The Hermès Years. The book contains archive images, essays, and interviews from the designer’s inner circle, depicting a series of quiet calculations that recalibrated the logic of major houses. While Marc Jacobs was inventing the Kanye-Murakami model of brand saturation, Margiela proposed an idea of luxury so concise that it almost dissolved into itself. These two ideas stand in a strong zoroastrian contrast that extends into today’s market. For while the digital context has stoked a desire to be hyper-recognizable, it has simultaneously made anonymity ever-more luxurious.

In September 2001, Margiela presented his Hermès womenswear collection at a “walking dinner” at Axel Vervoordt’s “M.C. Escher” building, where models of diverse ages nearly disappeared among the standing room of the guests. Like many things Margiela, it utilitized the power of innocuousness – a fashion that evaporates into a faint yet radical spore in the atmosphere. Some revolutions are quieter than others, albeit equally effective. As Dumas himself would later reflect in an interview with Sarah Mower: “They were expecting blood!”